Carissa’s World: How a Self-Effacing Girl from Kaimukī Surfed Her Way to Olympic Gold

Carissa Moore has become a beacon for a state, a people and a legion of young empowered women, without losing herself in the game.

It was a long lull, 101 years if you count back to the first time Duke Kahanamoku proposed adding surfing to the Olympics.

Looking at it that way, it felt almost ceremonial, the nearly 10 minutes on a stormy July day in Japan when neither surfer in the women’s final heat of the Tokyo Olympics could pick up a wave. It was Duke’s lull. To let the moment sink in. And, perhaps, to set the stage for Carissa Moore.

But in a sport where fortunes can be upended in 10 seconds, the long void filled with typhoon whitewater mostly seemed ominous—Moore had barely staved off weather-assisted upsets in both her semifinal heat an hour earlier and her third-round heat before that.

“A beach break is always challenging, not like a reef break, where the wave comes in the same place every time,” Moore recalls when we speak later. “And a typhoon swell meant a lot of current, so it was really hard to pick a spot. It really leveled out the playing field.” Throughout the Olympic surf heats, she adds, “you had really good surfers who didn’t get the right wave that meant other surfers, maybe not as skilled, could take a better one.”

In the semifinals, playing the underdog, host Japan’s Amura Tsuzuki came gunning for Moore with the advantage of having grown up surfing Tsurigasaki Beach, the Olympic site. Tsuzuki knocked out Moore’s nemesis Tatiana Weston-Webb, the Kaua‘i surfer ranked No. 4 in the world, then top Australian threat Sally Fitzgibbons.

In the semifinal, Moore was leading with a score of 8.00 to Tsuzuki’s 7.43. And then the ocean kicked up like a washing machine for 10 minutes. These were conditions no recreational surfer would go out in, and since playing defense was futile, Moore grabbed the next promising piece of storm surge to boost her score. When her gamble to leave Tsuzuki free in the last 10 seconds paid off, she had an hour to recharge before a physically grueling final. It would feature even worse conditions.

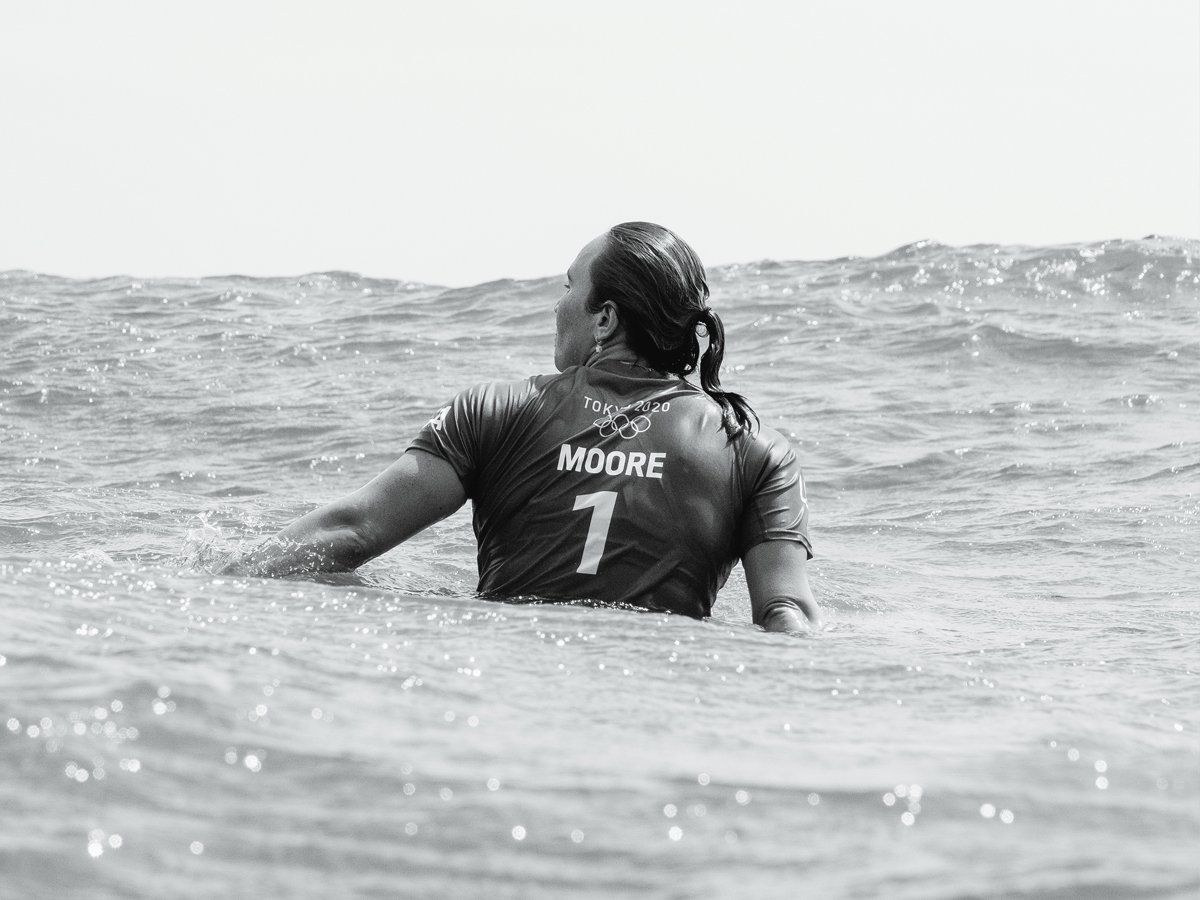

Less than two months after winning gold in Tokyo, Moore slashes her trademark cutback en route to a fifth WSL World Title on Sept. 14 at Lower Trestles, San Clemente, California. Photo: Tony Heff, Courtesy of World Surf League

As typhoon surf pummeled Tsurigasaki, Moore carved out sections rather than entire waves, a strategy that paid off in tight heats. Photo: Ben Reed, Courtesy of International Surfing Association

“ You had really good surfers who didn’t get the right wave that meant other surfers, maybe not as skilled, could take a better one.”

One of the signs of greatness is to make the extreme end of performance seem natural, inevitable, ordained—the kind of calm and equanimity that attended Moore at Tsurigasaki. That’s the aura of the girl from Kaimukī, who still surfs Kewalos, the raggedy urban Honolulu wave popular with the everyday surfer before and after work and on lunch breaks. A populist choice, not glam like Pipeline or Sunset, Kewalos also felt like a strategic choice. Easy to access during pro surfing’s COVID-19 year off, away from the North Shore’s celebrity spotlight, its fluky pop-up faces bear some resemblance to Tsurigasaki’s.

Kewalos kind of sums up where Moore is coming from these days. The right personal choice that ends up being the correct strategic choice also fits with her open-hearted and seemingly uncrafted public image.

Equilibrium like that doesn’t come easy or all at once, of course. In a bit of an oxymoron, finding the right balance in sports is an ongoing and never-ending process. Solo sports are psychological mindfields, as the Summer Olympics highlighted. Add in a yearlong pro circuit and its injuries and traveling-salesman lifestyle and you almost wonder why they do it—especially after seeing the public misery of fellow Olympians Naomi Osaka and Simone Biles when they spoke out about mental health issues.

Moore’s felt the pressure since she was 11. She won nearly a dozen junior surfing titles; at 16 she was the youngest ever to win a Triple Crown of Surfing event. At 17, in 2010, she was pro surfing’s female Rookie of the Year and at 18 was the youngest ever to win a world title, male or female. More world titles followed in 2013 and 2015.

But she faced criticism when she didn’t win world titles in 2016, 2017 and 2018. A high standard to be held to, perfection, but especially in surfing, a male-dominated sport with a bro’s prurient male gaze and commentary embedded in its DNA—and lucrative sponsorship opportunities.

As in the case of many a female athlete, it sometimes seemed that Moore’s body of work wasn’t the problem; it was that she didn’t wear a thong and play the coquette. To some, that wasn’t helping market the sport of “two girls for every boy.” For years during her heats, it seemed, the cameras lingered on other performers’ anatomies—or, just as often, those of girls on the beach, often planted there by swimwear sponsors.

“I never make those ‘hottest surfer girl’ lists,” she told ESPN’s Audrey Cleo Yap in 2015, one of a spate of interviews where she opened up about struggles including binge-eating and insecurity—but also about solutions. Candid and paired with her own practical homespun advice, her words sent shock waves through the surfing world and turned Moore into a positive body image spokesperson. “It used to bother me because all of my peers were on them [on advertisements], and I would look at myself and be like, ‘Why am I not hot? Why am I not beautiful?’” In the end, she says she decided, “I don’t care. … It’s all about balance for me, and that’s translated to every part of my life.”

The last couple of years of semi-successful striving for gender equity in sports was led by the U.S. women’s soccer team. But in surfing, litigious Northern Californians also demanded the Mavericks big-wave contest be open to women—and to pay them equally. Their victory in part spurred the World Surf League to charge ahead on the issue instead of lagging or resisting. At the Olympics, a conversation sparked by several female athletes turned to how women’s bodies were marketed. Why do women gymnasts wear such revealing outfits? Men don’t. The uniforms are mandatory, chosen along guidelines from the same U.S. gymnastics association that had overlooked and denied sexual abuse of these very women by their longtime team physician. It all became prime-time fodder after Simone Biles faltered on a vault and then withdrew.

Because Moore had taken her stance years earlier, she was prepared for what might’ve been intrusive questions, including one from an NBC Olympics interviewer right after she’d won a tough heat and was about to face another. Nobody asks Tom Brady about his body image before he takes the field for the Super Bowl, but for Moore it’s part of a role she’s accepted and takes seriously.

In the Olympics you felt the power Moore gained by taking control of her narrative in 2015. She’d defined herself. When you stand for something so clearly, you don’t need to say it all the time. She’s not a mannequin or human billboard, but by gracefully handling the questions—or firmly deflecting them when inappropriate or badly timed—she makes it easier for others without her power to do the same.

This dovetails naturally with her representing Native Hawaiians and the legacy of surfing’s ambassador, Duke Kahanamoku, to whom she is increasingly compared. “I think it’s crazy to be mentioned in the same sentence as Duke Kahanamoku,” she says. “I’m super honored to be a small part of his story. To be a Native Hawaiian and to represent our sport, Hawai‘i’s sport, and to bring gold back to our home, is something I feel very honored to have done.”

Photo: Aaron K. Yoshino

“I think it’s crazy to be mentioned in the same sentence as Duke Kahanamoku,” she says. “I’m super honored to be a small part of his story. To be a Native Hawaiian and to represent our sport, Hawai‘i’s sport, and to bring gold back to our home, is something I feel very honored to have done.”

It wasn’t so long ago that World Surf League’s own commentators would fill dead air time by speculating about Moore and how she differs from other competitors. Was it that she was “streaky,” “spacey,” even “flaky”? Or was it to do with her being Native Hawaiian? Was that aloha, the way she actually seemed to go out of her way to befriend competitors? Or was it (the male commentator’s voice deepening) a failure to go for the jugular?

Moore knows how to use her example to make a statement without calling a press conference. One of the best examples was during the 2021 tour, when she frequently chose to stay in a COVID pod with her friend and greatest rival in bigger, heavier waves—France’s Johanne Defay.

Defay’s story is a flashpoint of surfer feminism. The most powerful sponsor, swimwear giant Roxy, dropped the rising star in 2014 months before she turned pro. Getting dropped wasn’t just a matter of not appearing in advertisements or getting a monthly check. Sponsorship meant tickets to faraway tour events, hired cars from the hotel to the beach, food, coaches and, of course, surfboards. Suddenly she had to pay for everything herself.

Controversially for a rookie, Defay went public with Roxy’s rationale: “They said, ‘Oh, you don’t look this way, like, for pictures.’” According to an Associated Press story in the run-up to the Olympics, Defay went from a team-hired car ride to a contest to a two-hour trek on a bus. With her surfboards.

In response, France’s star surfer Jeremy Flores generously bankrolled Defay’s rookie season—an action that kept the spotlight on Roxy and other advertisers. And in 2021, Moore shared her pod pad with Defay, which meant other things came easier, too.

SEE ALSO: Surf Fans Will See Lots More Action on the World Surf League Tour in 2020 and Going Forward

People really took notice at the last WSL stop before the Olympics, the Lemoore Surf Ranch. An artificial-wave machine located in California’s bleak Central Valley, created by a group led by modern male surfing’s all-time great Kelly Slater, then sold to the WSL, the Surf Ranch is the only wave the WSL actually owns outright. (An interesting concept in itself, the technology seems a key to WSL’s morphing into an entertainment company.) Good soldier Moore threw herself enthusiastically into the wave’s 2018 debut and promotion. In the contest, the wave’s unnatural precision and longevity—it goes on and on and on, requiring move after move after move—suited Moore perfectly, while others, men as well as women, found their repertories of moves exhausted. Moore won its inaugural tour contest with elan.

By 2021, surfers had logged more time on the artificial wave and felt more comfortable. Leading in the standings and with a world title and a gold medal on her mind, Moore should have, in conventional sporting wisdom, avoided close company with her rival. But there she was with Defay and team in their rented suburban house, cheerily posting social media footage of their dinners and hangouts. Two top rivals, one comfortably subsidized, the other scraping by, goofing and washing dishes side by side? What was Moore thinking?

Maybe something like this: We’re in this together. We can show our solidarity. Those who have it good can lend a helping hand. We can compete without hating on each other. We can be friends who surf. Oh, and maybe this, too: Here we are, the two girls who once upon a time you wouldn’t sponsor. Look at us now!

Of course, when Defay went on to actually beat Moore in an epic head-to-head final, you know what some in the surf world said: See what happens when you give up your front-runner status and perks to some poor girl coming up? She takes your title!

At the Olympics, Defay would join Flores in representing France.

he mystery of Moore is compelling. She doesn’t go for the jugular; she goes for the joy. There’s something there, a glow when she emerges from the sea and a mindfulness when she pauses to think before answering the typical, “How was it out there?” question. She wants to give an honest, straightforward answer, but not before considering all the angles. Then, with a shake of her hair and a brilliant smile, she delivers—and the sun shines.

It’s the sunny smile, but also the consideration, the anti-glitz, the naturalness of her beauty, that seems to have made her a magnet for young women around the world. (And some not so young.) It’s become clear she carries their affection with care. And so she’s very aware, and wary of, any attempts to cram her into someone else’s narrative.

“When you’re an athlete it’s just brought to a head because people are talking about it. But mental health and taking care of yourself is super important for everybody.”

Photo: Aaron K. Yoshino

By 2019 it became clear that Moore had her own storyline in mind.

The first step in her comeback was returning to dominant form. She had plans to get to Tokyo, too, and with two wins and two runner-up finishes she captured her fourth world title and qualified for the Olympics. Her three-year drought over, she started off the 2020 season (actually in December 2019) by reaching the finals of the Lululemon Maui Pro, which was moved to O‘ahu’s Pipeline for the last day due to a fatal shark attack on a fisherman at Honolua Bay.

It was the first time the men running professional surfing had ever let the women surf Pipeline in competition, even though it’s the world’s best-known and most-storied wave. Though she lost to Tyler Wright in the final, their historic performance led the WSL to promise that it would give women a regular place at this table. (There was pressure coming from the City and County of Honolulu, too.)

And then, just like that, Moore announced she was taking 2020 off, except for a couple of non-tour amateur surfing events required for the Olympics.

Got that? The world champ, having returned to form, silencing her critics and surfing Pipe professionally, was going on hiatus.

SEE ALSO: Field Notes: These Surfers Get Up Before Dawn to Catch the Best Waves

As we all know, the entire world joined her.

She wanted time, she said. Time to be herself, to be with her husband, Luke Untermann, a Punahou classmate she married in 2017. She wanted off the globe-trotting treadmill. There were grumbles and rumbles that she was letting the pro circuit down just as it was pushing (again) for higher visibility under new leadership.

But it was her call. “The last few years, I definitely feel I’ve grown up a lot,” she says. “More like coming into my own, feeling comfortable in my own skin. Learning to listen to my intuition and my gut and my heart. Sometimes that’s not what everyone else wants for me, but when you listen to yourself, it tends to turn out the right way.”

No one could have guessed how this would turn out. First, she showed up for a non-WSL-tour challengers event, in January, and won it—a strategic move to assure she could step right back on tour in 2021. Then, as she prepared to disappear into private time, COVID-19 came along to change everything for everyone.

“The universe said, everybody has to slow down,” she says.

Asked about how her sabbatical compared with the drama around Naomi Osaka and Simone Biles, she takes a careful breath. “I think that everybody goes through their own things emotionally and mentally. Not just with sports, or with athletes. With life. Life is hard. As an athlete I think maybe it’s exemplified; we’re under a spotlight, it can feel … ” Another careful pause. “When you’re an athlete it’s just brought to a head because people are talking about it. But mental health and taking care of yourself is super important for everybody.”

Then there was representing Hawai‘i. The WSL honors surfing’s origins by letting locals surf under the Kingdom of Hawai‘i flag. Pre-Olympic news coverage homed in on the desire to do the same in Tokyo and Moore indicated she was in favor of the idea. But when the International Olympic Committee dismissed the petition, that was it. Though she and John John Florence did wear their Hawaiian flag patches, there would be no John Carlos moment.

I ask her, wishfully, if being out in nature helps balance the stresses. “Yes and no. I think we still go through the same struggles. There is something so beautiful about the ocean and yet … it takes a toll.”

Part of the cost is dealing with the constant self-interrogation. “I always ask myself, what does success look like? What should you be doing? It’s hard to separate yourself from the results, sometimes.”

That’s why the break was necessary. “It was kind of going against the grain. Like Simone, I took time off, mine in 2020 because I felt like I needed it. It wasn’t what everyone else thought I should do at the time. But I wanted to come back and feel refreshed and really love what I was doing.

“You can’t just go, go, go.”

Mission accomplished. The act of having detached herself publicly before the pandemic seemed to supply extra clarity. Sabbatical over, she joined the pandemic-challenged 2021 WSL pod tour, embracing its gypsy caravan of pro surfers living in isolation, sans crowds and parties, then making quick flights home.

During this year’s pandemic season, she says, “Everyone had to adjust their expectations, just deal with life-changing events, and forget the idea of having any kind of normal existence.” A sigh. “Life, it can be tricky at times. You just have to go and have an open mind and go with the flow when things don’t go the way you expect them to.”

Moore thrived on the go and the flow. She made the cooped-up quarters and barnstorming seem fun, and of course there was solidarity with her fellow women. Coming into the break for the Olympics she was again ranked No. 1.

Photo: Aaron K. Yoshino

Early in the Olympic final showdown, a nine-minute cauldron of unsurfable seas again seemed to favor the challenger, South Africa’s 6-foot-1-inch Bianca Buitendag, if only because neither surfer could get started. “The conditions were just really challenging,” Moore says. “Conditions were breaking down, seas getting bigger and lumpier.”

One thing was certain: Olympic gold wasn’t going to be decided by a 0.50 to 0.00 score. That would be like a Super Bowl playing to a shutout decided by a coin toss. Moore had to take charge, somehow, before Buitendag capitalized on this perfect recipe for an upset.

Under Japan’s COVID-19 protocols, much stricter than the WSL’s, the Olympics had stripped the world’s top surfers of their support systems: personal coaches, entourages, family members. As one used to traveling with husband Luke, father Chris, coaches and, occasionally, friends, Moore might’ve been at a disadvantage if she hadn’t already tested her independence.

“It was definitely different,” she says. “I would’ve loved to have had my family, the ones that were going to come, and maybe some of my friends, but at the same time it was simple. It was simplified. It was the ocean. It was literally going out and surfing. It was: ‘Hey, let’s go to the beach today.’”

The official U.S. Olympic surf coach, Brett Simpson, was perfect for the role. “He had a lot of experience competing, and had been a champion on tour,” she says. “He’d competed at Tsugi a few times himself. He knew how to read conditions and translate them to a plan. He’s just a great human and a great coach.”

Before heading out into the final, she did get one helpful long-distance boost. “My dad texted me: ‘I know it’s going to be challenging, don’t get frustrated, be resilient, keep figuring it out. Trust it. There’s going to be waves.’” She laughs. “I was either going to ride or die by the plan.”

Moore broke the scoring lull by going after pieces of waves in the whitewater. The first two were so violent she simply dropped in and pulled right out, flying out over the top. But the points began to add up, 3.67 to 0.00, as Buitendag still hesitated. “It can be kind of nerve-wracking and stressful at times,” Moore says of this period, “but that’s the rhythm of the ocean; you just got to move and groove with it. Be patient. It’ll come.”

It came—enough of a wave to carve out a single full-on performance turn that boosted her score to 6.57 to Buitendag’s 0.30. “There is a little kind of surrendering when it’s that difficult,” she says of the moment. And she recalls thinking, “‘Hey, all I can do is my very best and the rest is up to Mother Nature. Just surrender to the uncontrollable and do what you can.’ In that way I bought a little peace.”

She picked out another wave and as it finished, a rainbow broke out. Everyone watching seemed to think the same thing: Hawai‘i was sending her its aloha. Cowbells ringing from the U.S. team on the beach preceded the score: 7.33. Her tally now at 10.73 to 0.80, Moore let loose, putting on a personal Ode to Joy of Surfing, finding wave after wave, showing the world.

Arms raised in the V for victory, Moore rides the foam ball before dropping prone and cruising in, head perched on her fists—the first Olympic gold medalist in women’s surfing. Photo: Ben Reed, Courtesy of International Surfing Association

She skimmed back to shore in a trance. “I think it was kind of almost disbelief. How did that just happen? So much could not have gone my way. I almost lost in the semifinals. I mean I barely made it. I was very grateful; I almost felt I had a little love from the wave.”

Moore and the rest of the team never got to the opening or the closing ceremonies and had only one visit to the pared-down Olympic Village. But, she says: “I had so much fun with the team. Even though we didn’t go to the opening we put on our outfits and had our own ceremony in the house.”

She also had to self-award her gold medal. Still, having faced a weeklong media blitz of morning shows and interviews, did she feel the gold changed anything? “I hope people can lead with their hearts and be able to stand with the gold medal to share the aloha way of life,” she says in a rush, “to treat others with kindness and empathy and to put yourselves in other people’s shoes, to be vulnerable, to treat others and welcome them with unconditional love.”

She pauses, on this long call in a week when she’s preparing to go for her fifth world championship. “I hope that it sparks someone else to take their own passion or to get on a surfboard for the first time. I hope it will encourage people to remain authentic to themselves. I know there’s something in this crazy world that’s trying to mold them into something that they’re not. I want them to know there isn’t one specific mold and we aren’t meant to fit it.”

In September Moore headed into a one-day showdown with the top five points leaders at Trestles in California. The WSL had changed the championship format; a media company at heart, it decided to amp things up by making it a shootout (even as it launched a reality TV show about surfers trying to make the tour). Without the changes, Moore would’ve virtually wrapped up her fifth world title on points. The surest sign that a generational talent has arrived is when they change the rules to make it harder for you to succeed. But she’s stoic about it.

“The new format is not a surprise,” she says. “I had heard all the conversations for a while. Who knows if it’s the right format for surfing.”

It did produce a familiar showdown. After the knockout rounds, Tatiana Weston-Webb, ranked No. 2, emerged as the challenger. Moore nearly had her season of work go down the drain after losing a close first heat. Again, summoning the dragon of Tsurigasaki, back to the wall, Moore routed Weston-Webb in the second heat. With a tiebreaker set, both surfers had given the WSL the finale it had hoped for—but a fiery Moore closed the door emphatically on her challenger to win her fifth world title. Again, her ability to summon inevitability made for an otherworldly performance.

“To be honest, I’m a bit broken today,” she says after her staggering run of 8-point scores that brought her back from the brink. “I can barely move.” Still, she is looking forward to the league’s 2022 plans to kick off the season in Hawai‘i with women’s and men’s events at Pipeline and Sunset, a first. Plans also include Tahiti’s Teahupo‘o, another first. “It’s going to be super intense.”

That she had something to do with it went unsaid. But it felt like more proof that we’re living in Carissa Moore’s world.

“ I know there’s something in this crazy world that’s trying to mold them into something that they’re not. I want them to know there isn’t one specific mold and we aren’t meant to fit it.”

SEE ALSO: Silver Surfers: Meet 5 Surf Legends Who, in Their 60s and 70s, Still Hit the Beach