By Christine Hitt | Photo composites: James Nakamura

* * *

* * *

By the time my mother died at 62, she had wrestled with health problems all too familiar among Native Hawaiian families. She survived a difficult battle with breast cancer, struggled with her weight, took insulin shots for diabetes and then developed Parkinson’s disease.

My mother’s story reflects what some Hawaiian families face every day. It’s tangible evidence of the still traumatic effects of the Islands’ Western colonization more than 200 years ago. Hundreds of thousands of Native Hawaiians succumbed to infectious diseases brought to the Islands starting with the arrival of Captain Cook in 1778; today chronic diseases are taking a toll.

“Native Hawaiians compared to other ethnic groups here in Hawai‘i bear a very disproportionate burden of many chronic diseases, even mental health issues,” says Dr. Keawe‘aimoku Kaholokula, a Native Hawaiian who chairs the Native Hawaiian Health Department at UH’s John A. Burns School of Medicine. “Among the chronic diseases we face are issues around diabetes and heart disease, for example, and risk factors such as obesity and high blood pressure. We’re even seeing now with Alzheimer’s and other dementia an increase, if not higher rates, among Native Hawaiians.”

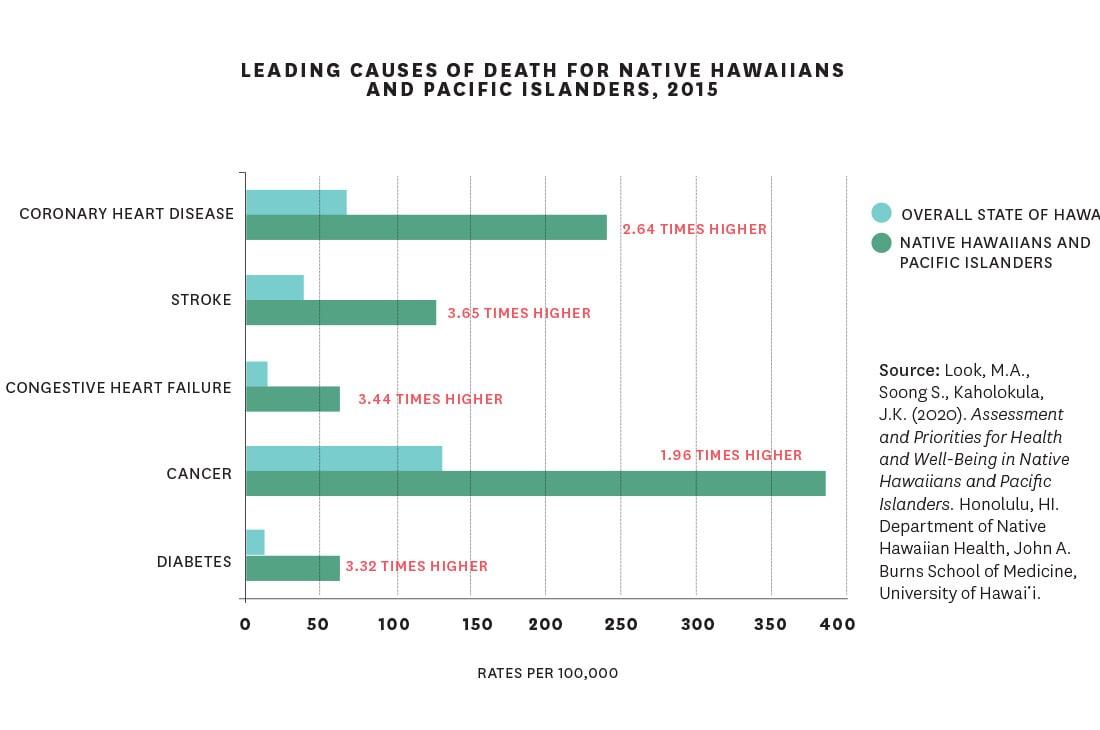

These diseases occur in the general population, too. But Hawaiians are at least three times more likely to develop chronic diseases than other ethnic groups in Hawai‘i, and the onset of those diseases occurs when they’re a decade younger, according to a 2020 JABSOM study co-authored by Kaholokula. These illnesses also make Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders more vulnerable to severe COVID-19 infections and death.

Other recent UH studies are also disturbing: Hawaiians with colorectal cancer are twice as likely to die from sepsis. Hawaiian women with breast cancer have higher rates of inflammatory breast cancer, an aggressive form. Older Hawaiians have twice the risk of developing gout.

The average lifespan of Hawaiians shows steady improvement over the years—74.3 years in 2000 versus 62.5 years in 1950. But even here, Native Hawaiians lag behind the rest of Hawai‘i’s population. They’re dying younger than everybody else by about six years.

Hawaiians have suffered health disparities since the days of Captain Cook. With Westerners came a long list of ailments—measles, smallpox, cholera, Hansen’s disease, venereal diseases, tuberculosis, the plague. Infectious diseases decimated the pre-contact population estimated around 700,000: By 1900, there were just 37,656 full and part Hawaiians, according to the U.S. Census.

Today it’s not infectious diseases but diabetes, cardiovascular disease, stroke, congestive heart failure and cancer that Native Hawaiians disproportionately struggle with. In a state where the drowsiness that can follow a large meal is jokingly called a kanak attack, a diet high in sodium, saturated fats and processed foods seems an obvious culprit. But Hawaiians’ higher rates of chronic disease can’t just be pinned on individual choices.

“By 1893, the Hawaiian Kingdom was overthrown, and other ethnicities and people came to power. The world changed for the Hawaiians. All of a sudden, in their own place, they were second-class. That really impacts us today,” says Dr. Gerard Akaka, The Queen’s Health System vice president for Native Hawaiian Affairs and Clinical Support. He’s also medical

director of the Native Hawaiian Health Department at Queen’s.

“As far as Hawaiian health, in general, I think they’re still dealing with things and the way it comes out is low aspirational goals. There’s still dysfunction, they’re still not eating the right foods. Hard to put my finger on it: Is it stress eating or is it historical trauma over the years? I’m sure it’s all baked into why the health did not really improve since the 1980s.”

Obesity is one cause of many chronic problems. Akaka is Native Hawaiian and has seen how preferences for Spam, mayonnaise, ice cream, rice and Coca-Cola have risen, sometimes driven by what’s most affordable. An upbringing that teaches not to waste food, because it’s uncertain when the next meal is coming, affects eating habits as well. And family gatherings for birthdays, graduations, weddings, parties and funerals typically include buffets of high-caloric foods.

“We love to eat. Eating is part of a celebration culturally. That’s how we connect and reach out and fellowship with our loved ones,” Akaka says. “It’s about really changing things that Hawaiians love and hold dear.”

He suggests drinking water instead of soda, stepping away from the table when you’re 80% full, and walking, gardening or doing any physical activity. But changing behavior is only part of the solution. The social determinants of health—the economic, educational, environmental and social conditions that a person is born into—affect their lifespans and the quality of their lives.

“A lot of our Native Hawaiians live in what we call biogenic environments,” Kaholokula says. “[Those] environments just lend themselves to higher rates of obesity with less access to fresh fruits and vegetables, less opportunities for physical activity, or even being unsafe or having more exposure to toxins.”

Where people live can affect their health. A CDC report published in 2018 noted that life expectancy in Hawai‘i Kai was 87.3 years, while in Waimānalo it was 72 to 79 years. In Wai‘anae, where Hawaiians are concentrated most, it was 74.9 years.

“I’ve seen too many of my neighbors and friends in Papakōlea who have had complications due to diabetes and many of them have passed,” says Puni Kekauoha, a lifelong resident of the Hawaiian homestead. “We know that … especially in the Hawaiian community, the number of kūpuna that are aging with Alzheimer’s and age-related dementia is like off the chart,” she says. “It is alarming. It’s scary.”

The JABSOM study describes a hale with four corner posts. Each represents the framework that holds the hale together and what’s needed to create systemic change, such as cultural spaces for practices and beliefs, programs that ensure fair and equitable treatment, access to nature and food sovereignty, and education about healthy food choices and how to incorporate traditional meals. “The ability of Hawaiians to adhere to their ancestral knowledge is central to their identity and social relations, and is intimately tied to their physical and emotional well-being,” the report states.

In other words, health equity for Hawaiians won’t be achieved through a Western lens. Hawaiian cultural values must be included. And around the state, many values now are, with different initiatives bringing a multifaceted healing process to Native Hawaiians.

In 2019, Kaholokula led a JABSOM team in studying hula as a means to heal maladies. The five-year study found that hula reduced hypertension in Native Hawaiian participants: Their systolic blood pressure dropped by an average of 17 points. In Papakōlea, Kekauoha is the senior vice president of the nonprofit Kula No Na Po‘e Hawai‘i, which provides residents with health education and activity programs—including hula classes inspired by the JABSOM study to help stave off the cognitive decline of dementia.

The Queen’s Health System has also embraced hula as a way to lower hypertension. Anela Lockwood started twice-a-week virtual hula sessions with Queen’s in January. The 34-year-old records her blood pressure daily and reports her numbers to the program coordinator once a week. “I just really wanted to be a part of it because I’m Native Hawaiian and I have high blood pressure,” she says. Her 69-year-old mom also has high blood pressure and signed up as well. Both danced hula many years ago and say they enjoy going through the six-month program together. “I think the most beneficial part of it is that it’s a group exercise. Also, it’s just fun,” Lockwood says. “It’s not like one of those fitness classes where you eventually feel like it’s a chore to drag yourself to the gym.”

Another healthy lifestyle program teaches people how to make poi. Such culturally grounded activities are preferred by Native Hawaiians. But Kaholokula says it’s a challenge to get more of them into the community. And sustaining the programs once they’re in the community is another issue.

The Queen’s Medical Center, founded by Queen Emma and King Kamehameha IV in 1859, started its own culturally adapted program in 2016 that brings community health workers known as “navigators” onto a patient’s health team. Navigators understand that in the Hawaiian view, creating a healthy individual requires looking at the body, mind and spirit. They serve as liaisons among the hospital, community services and patients. The navigator program has helped to reduce Native Hawaiian readmissions to the hospital; Akaka would like to see it expand to other locations. “I just want to scale up so we can catch as many Hawaiian patients who come to Queen’s as possible in our primary care clinics,” he says.

His Native Hawaiian Health Department is investing in technology he hopes will help patients live longer. Now, patients track their blood pressure manually. A new system will send that data electronically to a doctor, who can watch it remotely in real time. Akaka hopes to broaden the program to include data from diabetic patients. “It’s going to help Queen’s reach out to patients better and ultimately it’s going to help Hawaiians who use it,” he says. His goal: to reduce the gap between Native Hawaiians’ average lifespans and that of the rest of Hawai‘i’s population from six years to three within a decade.

It’s urgently needed. “I’m hungry to achieve that aspirational goal. … It’s ambitious and bold, but we’re going to do everything we can to achieve it,” Akaka says. “I hope that Hawaiians who might be reading this will know that there’s work being done.”

A freelance writer from O‘ahu, Christine Hitt has been covering our Islands for 15 years. She’s a Kamehameha Schools and University of Hawai‘i graduate, and her work has been seen in the Los Angeles Times, SFGATE, Flux, Mana, HAWAI‘I and HONOLULU, among others. She often focuses on Native Hawaiian culture and issues.

A freelance writer from O‘ahu, Christine Hitt has been covering our Islands for 15 years. She’s a Kamehameha Schools and University of Hawai‘i graduate, and her work has been seen in the Los Angeles Times, SFGATE, Flux, Mana, HAWAI‘I and HONOLULU, among others. She often focuses on Native Hawaiian culture and issues.