Can We Return to Ahupua‘a?

A movement is underway to resurrect the traditional Hawaiian land division and management system to better care for the ‘āina, water and people.

“This conversation is a bold one, but it’s time to be bold.”

—JOHN DEFRIES, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, MAUNA KEA STEWARDSHIP AND OVERSIGHT AUTHORITY

U

Ua mau ke ea o ka ‘āina i ka pono. The life of the land is perpetuated in righteousness.

It’s the official motto of our state, the words of King Kamehameha III, and its message lies at the heart of a bold movement taking shape in Hawai‘i.

A prominent group of leaders has organized to resurrect the Islands’ traditional ahupua‘a and konohiki systems. Their calling: to better care for Hawai‘i’s natural resources and residents.

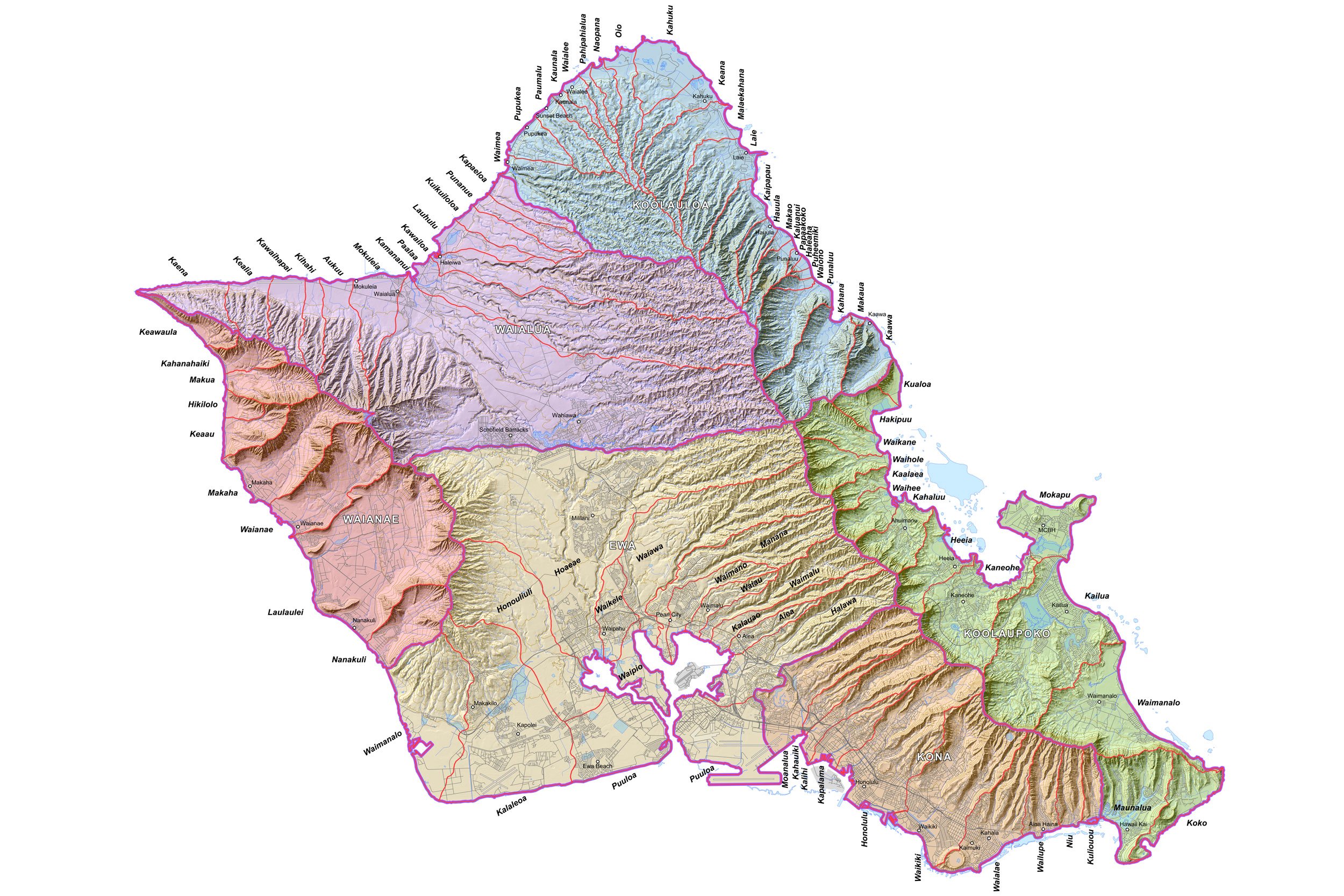

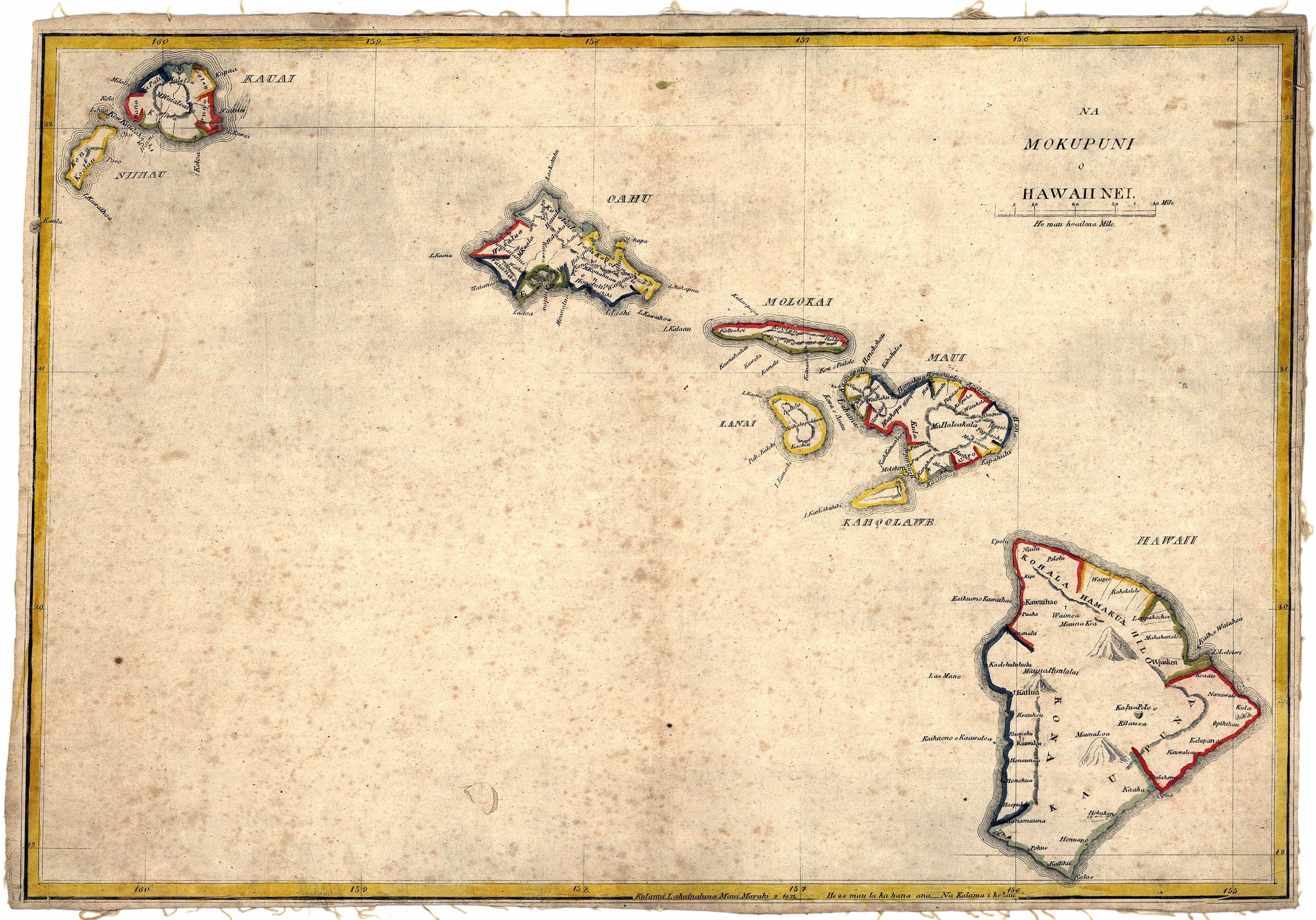

Ahupua‘a is a traditional Hawaiian land division and management system that took shape around A.D. 1200 and remained in place until the Great Mahele of 1848, when the Kingdom of Hawai‘i transitioned from a communal land system to one of private ownership. Its guiding principle is that land, water and all of nature are interconnected, so they must be managed synergistically, with care. Under the system, the Hawaiian Islands were structured into approximately 725 ahupua‘a, each being ecologically self-sustaining, and extending from the mountains to the sea, mauka to makai.

“In Hawai‘i’s history, water was considered sacred. The rains fed rivers and streams, which flowed down from the mountains,” says Kamana‘opono Crabbe, one of the movement’s organizers. “Our ancestors were highly knowledgeable of that system and preserved Hawai‘i as a pristine habitat.”

Konohiki was the governing system of ahupua‘a, led by a chief and council of leaders tasked with managing natural resources to ensure people had ample food, clean water, places to live and more. Leaders of each ahupua‘a had to intrinsically understand and adhere to nature’s flow to successfully tend to watersheds, fishponds, forests and agricultural lands. Doing so ensured that invasive species didn’t run amok, fishponds weren’t disrupted, and crops were abundant.

“It was a symbiotic balance of making sure that if we take care of nature, it will take care of us,” says Stacy Ferreira, CEO of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, who took part in a recent talk about ahupua‘a.

While ahupua‘a and konohiki worked in Hawai‘i’s past, questions linger. Can ancient systems be applied in modern day Hawai‘i and coexist under the state’s current government? Likewise, would the people of Hawai‘i support going back to traditional Hawaiian ways of mālama ‘āina, or caring for the land?

How the Discussion Began

Conversations about ahupua‘a have been taking place through the Hawai‘i Executive Collaborative, a consortium of business, government and community leaders that devises solutions for the state’s most urgent problems. (HEC chairman Duane Kurisu owns aio, the parent company of HONOLULU.) HEC participants—essentially a who’s who of Hawai‘i leaders—have been meeting in recent years both at an annual conference and at organized “accelerators” as part of an overall effort called “Rediscovering Hawai‘i’s Soul.”

In January, a newly formed ahupua‘a team met for two days at an accelerator at the East-West Center. The resurrection of ahupua‘a was among four topics tackled by different teams of leaders representing a wide range of industries and organizations.

Yet such talks are nothing new. For years, Native Hawaiian leaders have been advocating a return to traditional practices to repair damage they say has occurred in modern times.

It came up in 2014, during the highly divisive debates over Maunakea. Critical of plans to construct the Thirty Meter Telescope atop a sacred mountain, Native Hawaiians accused the government of mismanaging Hawai‘i’s lands and natural resources. This led to other contentious discussions about the still-unresolved future of Hawai‘i’s Kingdom Lands, also known as ceded lands. Then in 2023, with government and other entities targeted for blame after wildfires tore through Lahaina, calls to resurrect the ahupua‘a grew even louder.

The argument: In Hawai‘i’s past, with ahupua‘a and konohiki systems in place, up to a million residents were able to live sustainably on the Islands, which is no longer the case.

“By compromising our watersheds and environment, we’re now importing the majority of our food, and water is scarce. The traditions of our ancestors are night and day from what government has implemented, and we’ve gotten out of harmony with how nature flows,” Crabbe says.

Time for Radical Change

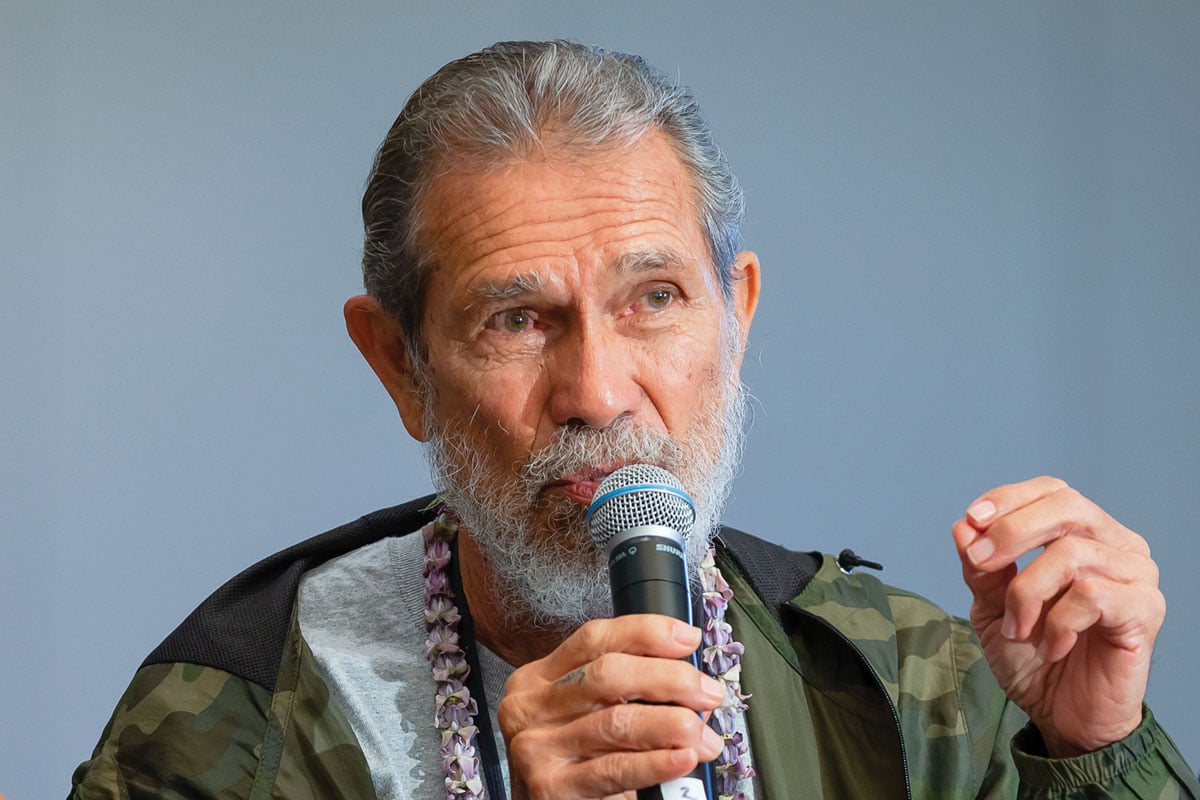

That was the resounding sentiment among the group gathered in January to discuss ahupua‘a and konohiki, including John DeFries, executive director of the Mauna Kea Stewardship and Oversight Authority and former CEO of the Hawai‘i Tourism Authority.

“This conversation is a bold one, but it’s time to be bold,” he said at the gathering.

It’s clear Hawai‘i’s most urgent problems are upending lives. The high cost of living and particularly the lack of affordable housing has led to an ongoing, dramatic outflow of residents—40,000 people in 2024 alone. And according to Aloha United Way’s 2024 “ALICE” report, 37% of Hawai‘i’s residents are considering leaving, while 4 in 10 residents are struggling to make ends meet. Hawai‘i also imports 90% of its food and goods, despite a statewide push toward sustainability.

As far as our ‘āina, it’s not healthy, the leaders say. O‘ahu’s Red Hill crisis revealed the vulnerability of our water systems when jet fuel leaked from an underground military storage facility into the freshwater aquifer, contaminating drinking water. And in Lahaina, unmaintained, overgrown vegetation was partly to blame for the quick spread of the wildfires.

“Individuals in our community feel they are no longer able to survive here or take care of their families, find jobs and places to live,” says Ulalia Woodside Lee, director of The Nature Conservancy, Hawai‘i and Palmyra, and part of the ahupua‘a team. “Our natural environment is facing challenges, too. We face consequences like the runoff of topsoil into streams and ocean, wildfires or fires near urban places like Lahaina, and agriculture crops are under attack from invasive bugs.”

Unless dramatic changes take place, these and other issues are likely to get worse, she and other leaders say.

“Can We Design a New Hawai‘i?”

It’s a question raised by Corbett Kalama, part of the ahupua‘a team and president and CEO of RESCO Inc., parent company of real estate firm Locations.

Under the traditional konohiki system, installing competent leaders was critical. Each ahupua‘a was led by a paramount or top chief (ali‘i nui) along with several councils of chiefly leaders (mau ‘aha ali‘i). They were selected, according to Crabbe, because of their good character (‘ōpūali‘i, na ‘auali‘i) and honorable stewardship of land, ocean, water and people. If the chiefs did not serve well, they were removed from power.

The goal of chiefs was to grow mana, he adds. They had to be na‘auao (enlightened, highly intellectual, virtuous, moral) with na‘au (the seat of the Hawaiian mind), and they had to exhibit hanapono (proper behavior, etiquette, protocol). They focused on the welfare of the people for the benefit of the community.

Not So Far-Fetched

While today, all of that may seem more idealistic than realistic, there are several examples of ahupua‘a practices in place. These are just a few:

In the early 2000s, The Nature Conservancy, UH and the state joined forces to clear invasive algae from Kāne‘ohe Bay’s coral reefs. They successfully vacuumed algae off the reef and brought in native sea urchins to prevent it from growing back. After considering the causes of the problem, they decided better management was needed upland as well, a key ahupua‘a principle. Community groups then set out to restore the health of the whole He‘eia ahupua‘a, providing a model for large-scale restoration through traditional Hawaiian practices.

“We’re restoring traditional systems, lo‘i systems, for the potential of growing food for the community,” says Hi‘ilei Kawelo, executive director of Paepae o He‘eia, a group that’s restoring the He‘eia fishpond. “Our inspiration, drive and passion is our history and what our kūpuna did. It’s an 800-year-old fishpond. We want it to work again, so the fishpond can feed the community and provide an ecological benefit.”

The Waipā Foundation on Kaua‘i, meanwhile, has been stewarding the 1,600-acre Waipā ahupua‘a, along Hanalei Bay, under a lease from landowner Kamehameha Schools. Through various programs, the organization cites its mission as restoring Waipā’s vibrant natural systems and resources through Hawaiian values and ahupua‘a practices.

And on Moloka‘i, Native Hawaiian activist Walter Ritte, part of HEC’s ahupua‘a team, says his organization, ‘Āina Momona, works under principles of ahupua‘a, managing land and water to ensure the health of the island’s ecosystem. (See story below)

But There Are Obstacles

Yet, even with motivated and organized community members, reinstating a complete ahupua‘a system—from mauka to makai, with konohiki governance—requires an overhaul of Hawai‘i’s current land systems, not a simple undertaking to say the least.

Hawai‘i’s lands are now owned and managed by multiple entities—government, trusts, businesses, and both large and small landowners. After the Great Mahele, landownership wasn’t parceled by ahupua‘a, so each ahupua‘a likely has multiple owners.

The state’s Department of Land and Natural Resources oversees nearly 1.3 million acres of Hawai‘i’s lands, beaches and coastal waters, along with 750 miles of coastline. This includes state parks, historical sites, forests, public fishing and hunting areas, and natural sanctuaries. DLNR also manages watersheds, along with the Board of Water Supply.

Along with state ownership, Hawai‘i counties and the U.S. government oversee thousands of acres of their own. Add to this the U.S. military, whose bases comprise thousands of acres; leases on some of those lands come up for renewal in 2028. Then, of course, there are large landowners like Kamehameha Schools and Alexander & Baldwin. Meanwhile, about 200,000 acres are designated as Hawaiian home lands, administered by the state to provide leased land to Native Hawaiians.

What About Ceded Lands?

Amid this complex network of landownership lies the unresolved, volatile issue of Kingdom Lands. Some 1.8 million acres of Kingdom Lands belonged to the Hawaiian Kingdom before the illegal overthrow of Hawai‘i in 1893. After being ceded to the U.S. in 1898, 1.4 million acres were transferred back to Hawai‘i in 1959 when it became a state. (The federal government kept 374,000 acres for military bases and national parks.) The lands were designated in a public trust intended to benefit the people of Hawai‘i and Native Hawaiians, and OHA was established in 1978 to administer 20% of the share of Public Land Trust revenues to Native Hawaiians.

Since 2014, OHA has been working on a Kingdom Lands inventory to ensure that Native Hawaiians get their fair share of revenues, but the group has run into numerous roadblocks while trying to compile an accurate, comprehensive list, says Ferreira, the agency’s CEO.

The issue over ceded lands ties into the ahupua‘a discussion because there will be no return to ahupua‘a without land. And because these lands were designated in a trust to benefit Native Hawaiians and the people of Hawai‘i, those pushing to reinstate ahupua‘a believe at least some ceded lands could potentially be utilized in this capacity. The leaders who convened in January discussed lobbying DLNR—whose domain includes a good portion of Kingdom Lands—to adopt “ahupua‘a or stewardship zoning,” as a feasible way forward.

DLNR: Partner or Obstacle?

Throughout the two days of ahupua‘a talks, DLNR’s stewardship of Hawai‘i’s land and natural resources was questioned. It’s an issue that last year led some community members and lawmakers to call for the resignation of DLNR Chair Dawn Chang, citing mismanagement.

Chang was invited to the recent ahupua‘a discussion, but the legislative session kept her from attending. Nevertheless, in a later interview, she expressed her support for the adoption of traditional Hawaiian practices, saying she sees such methods as being “vital to how land is managed in Hawai‘i.” DLNR, she says, has numerous partnerships already in place with ‘āina-based community organizations—such as Paepae o He‘eia and Hui Maka‘āinana o Makana, which stewards Hā‘ena State Park on Kaua‘i—and wants to establish more. “I see ‘āina-based management as natural, instinctual and culturally appropriate,” Chang says.

As far as adopting a true konohiki system, though, that won’t be easy. Getting DLNR to relinquish control of its current management responsibilities is a hurdle, but Chang says she and others from DLNR want to improve the agency’s standing in the community through meaningful partnerships that allow groups to tend to lands and water where it makes sense.

“Native Hawaiians have not historically trusted the Department of Land and Natural Resources or government as a whole because we haven’t created an environment of shared responsibility for change,” Chang says. “To change that dynamic, we need partnerships with our communities. That’s historically been a challenge for government agencies, but as we move forward, we’re making a concerted effort so there is greater trust and collaboration to protect our resources.”

“The lessons learned from multiple generations of living here can provide us a guide and a path to help us care for the land and our community.”

—ULALIA WOODSIDE LEE, DIRECTOR OF THE NATURE CONSERVANCY, HAWAI‘I AND PALMYRA

People Have to Want Change

Along with untangling land issues, Paepae o He‘eia’s Kawelo believes the people of Hawai‘i have to support the ahupua‘a way of life, even if it means altering habits.

“We can restore the system and grow the food, but is the community ready?” she asks. “Will our eating habits shift? It might mean paying more for poi that’s cultivated in the community. It might be paying more for fish that comes out of the fishpond. If I didn’t believe that’s possible, we wouldn’t be doing the work—we’re banking on it.”

What’s Next?

At the end of the two-day accelerator, leaders set goals, including involving more key leaders in future conversations. Among those key leaders would be Chang, from DLNR.

“I welcome the opportunity to be at the table with them,” Chang says. “I’m optimistic there will be further opportunities for us to collaborate, talk story, share what we are doing. I know we’ll find that we all have a lot in common and can figure out how to maximize our limited resources for the maximum good for the people of Hawai‘i, and in particular, the Native Hawaiian population that has been disenfranchised by government for a long time.”

The group also plans to work with OHA as it continues to seek a comprehensive and accurate land inventory, which would bring clarity on Kingdom Lands. Those lands aren’t restricted as to how they’re utilized, unlike Hawaiian home lands.

Members of the ahupua‘a group agreed though that their objectives can’t be limited to advocacy for Native Hawaiians. The movement must benefit all of the people of Hawai‘i.

“Nurturing land is for everyone; so is the fight for it,” says Jon Osorio, dean of the UH Hawai‘inuiākea School of Hawaiian Knowledge.

Says Crabbe: “Hawaiians aren’t in the fight for ourselves. We’re looking out for the welfare of all the people of Hawai‘i.”

In the meantime, the leaders plan to study existing models of ahupua‘a at work to see what’s working and what’s not, and how they could be scaled up.

“We need to show everyone how we’re going to mālama our land, care for our precious water sources, preserve our oceans, and help all people thrive,” Crabbe says. “It worked in the past, so it can be done again. And we have to remember—to perpetuate righteousness, land must come first.”

Moloka‘i as a Model

by Walter Ritte, as told to Diane Seo

On Moloka‘i, a third of our food comes from subsistence activity, and for our subsistence economy to flourish, we need to care for our reef. We have the largest contiguous reef system in the country. It’s 30 miles, and it was dying because of erosion coming off the land. We had to stop the erosion. The late Hawai‘i Sen. Daniel Inouye and Gov. John Waihe‘e visited Moloka‘i and saw our fishponds, and we got support from both of them. So, more than 20 years later, we have a statewide group organizing fishpond restorations.

We’re working on a fishpond owned by Kamehameha Schools. There was a nursery, then after a big rain, mud came down the hillside and into the nursery. Thousands of baby fish died because particles clogged up their gills. For us to survive on Moloka‘i, we have to take care of all our fishponds and bring life back into the ahupua‘a. We’re working with Kamehameha Schools to help stop the erosion coming into the fishpond. We’re also creating a workforce development plan to build facilities to train workers.

The fishponds are not just to feed families; they’re also a nursery to stock the entire reef system. For us to have starches, we have to go back to traditional ways. So, we’re removing cows and invasives, planting Hawaiian plants, stopping erosion and letting rainwater soak back into the aquifer.

DLNR (Department of Land and Natural Resources) purchased the ahupua‘a next to us. We told them they have the same problems we had with our ahupua‘a, so they came to visit a few months ago and liked what they saw. They expressed interest in going to the state to ask for funding.

Back in the day, a million people could survive in Hawai‘i without harming the lands. People used to see me as an enemy. We stopped big tourist boats from coming, and we fought against West Moloka‘i development. But now people see what’s happening on O‘ahu and other islands and talk positively about what we’re trying to do. Hopefully, we can be an example. You have to show people there’s a way.

Aha Moku System

The movement to return to traditional Hawaiian practices of land and ocean management has a precedence. In 2007, then-Hawai‘i Gov. Linda Lingle agreed to establish an Aha Moku Council system on each island. Five years later, an Aha Moku advisory committee was formed under the state’s Department of Land and Natural Resources, with the goal of integrating Native Hawaiian values to sustain natural resources. Despite these efforts, the system was never fully implemented.

The Ahupua‘a Team

A group of leaders, part of the Hawai‘i Executive Collaborative’s Rediscovering Hawai‘i’s Soul effort, came together for two days in late January to discuss the return of ahupua‘a. Members of the group include:

- Kamana‘opono Crabbe, executive lead for Hawai‘i Executive Collaborative’s Rediscovering Hawai‘i’s Soul initiative

- John DeFries, executive director of Mauna Kea Stewardship and Oversight Authority

- Corbett Kalama, president/CEO of RESCO Inc., Locations’ parent company

- Duane Kurisu, chairman/CEO of aio, the parent company of HONOLULU

- Lynelle Marble, HEC executive director

- Jon Osorio, dean of UH’s Hawai‘inuiākea School of Hawaiian Knowledge

- Walter Ritte, Native Hawaiian activist and executive director of ‘Āina Momona

- John Waihe‘e III, served as Hawai‘i’s fourth governor from 1986 to 1994

- Ulalia Woodside Lee, The Nature Conservancy’s director, Hawai‘i and Palmyra