Local Online Grocer Farm Link Builds Up Hawai‘i’s Food Systems

Farm Link’s intrepid attempts to accomplish its overarching mission highlights the hurdles Hawai‘i faces in achieving food sustainability.

At Farm Link Hawai‘i’s warehouse on Waiakamilo Road, workers pack Hawai‘i Island lychee, Maui strawberries, poi harvested and milled in He‘eia, and red Cuban bananas from Hale‘iwa. Shelves are stocked with Maui-grown agave spirit and lip balm made in Mānoa with Kaua‘i beeswax and O‘ahu vanilla beans. It used to be if you wanted this kind of selection, you’d have to scour farmers markets, Chinatown, Foodland and Whole Foods. And you’d be lucky to find it all. Now, through Farm Link, a local online grocer, you can get it delivered to your door.

“The goal is having as complete a shop as possible, so that we can make it convenient for you, and that we’re supporting a whole food system, all the way from the raw ingredients to the manufacturers,” Farm Link CEO Claire Sullivan says. In a perfect world, everything sold on Farm Link would be grown in Hawai‘i or made with locally grown ingredients—but it’s going to take some time to get there.

The business’s 30-year mission—what it calls its “Big Hairy Audacious Goal” or “BHAG”—is taped to its warehouse’s cinderblock wall, detailing a utopia through Farm Link’s lens. There are 11 bullet points describing “what it will look like when we achieve our BHAG,” including: “Working agricultural fields, sheds, tractors, animals, and farmers are prominent across the Hawai‘i landscape and regenerative practices abound.”

It can feel incongruous imagining this agrarian ideal, when Farm Link’s current operations involve customers clicking through a website and finding produce in a cardboard box at their door the next day. But good luck finding anywhere else with as large a selection of local products. Maybe this is what utopia looks like when trying to improve what Farm Link founder Rob Barreca calls “one of the most complex systems that we interact with every day: the local food system.”

When Barreca left his job as a web designer in 2013 “to broadly do something in food and find some meaning in my life,” he says, he enrolled in the University of Hawai‘i’s GoFarm beginning farmer training course in Waimānalo. He sold what he grew, and when delivering produce to restaurants, he ran into classmates doing the same thing. “We all just drove half an hour, all did the back and forth with the chefs, and all had to deal with invoicing—it was so inefficient,” he recalls.

In 2015, he built what would become Farm Link, reaching out to growers who didn’t want to market, sell, deliver and invoice themselves. And he found buyers for their goods. In the beginning, that included Foodland and Peter Merriman’s restaurants.

Barreca remembers times when Farm Link had inventory that needed to move, and they’d call chef Jose Gonzalez-Maya at Merriman’s Monkeypod Kitchen in Ko Olina. “Ninety-nine percent of the time he would say, ‘Yeah, I’ll take it, name the price.’ I swear, I almost cried a few times—I was just so stressed.”

That sense of relief is what Barreca wants Farm Link to provide its producers. “We want to evoke those same feelings, like, ‘Oh my god, I don’t have to worry so much about how to be able to sell this thing and make a viable business.’ We just want to say, ‘We want to take that off your shoulders, and we’re going to figure it out.’”

BHAG bullet point: “Producers say that FLH is their preferred buyer because we pay the best, we’re the easiest to deal with, we connect them with other resources, we help them plan and grow, and we honor our commitments.”

Barreca was just starting to explore direct-to-door delivery for households with funding from Elemental Excelerator when pandemic shelter-in-place orders descended in 2020. Sign-ups for Farm Link exploded, and operations expanded from a 40-foot refrigerated container in a dirt parking lot in Hale‘iwa to a 5,000-square-foot warehouse in Kalihi. Annual sales of around $400,000 before the pandemic grew to $2.8 million in 2023, with more customers, producers, plus an in-house butchery program, a liquor license, and daily delivery service across O‘ahu.

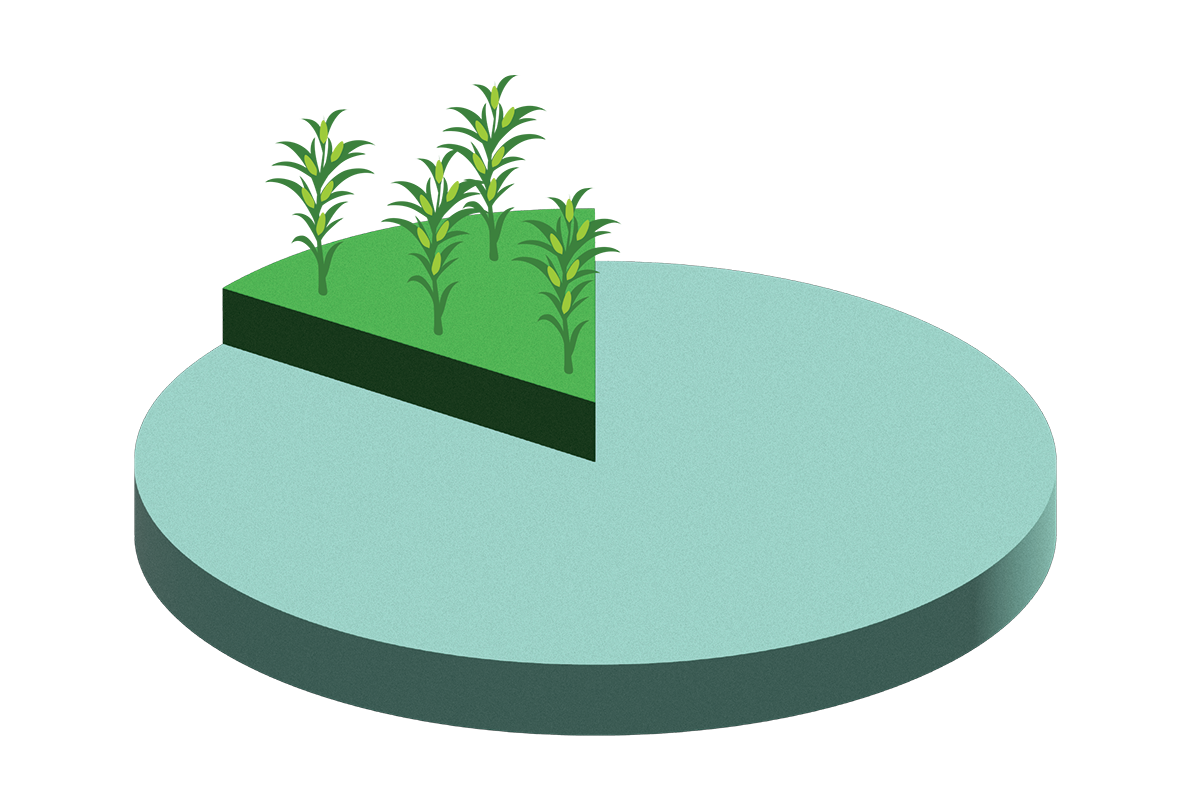

Still, Sullivan estimates that only 0.3% of O‘ahu’s $3.3 billion total grocery sales are made through Farm Link. And supply on Farm Link can be inconsistent. Some staples like bananas and tomatoes are not always available, a reflection of the tenuousness of Hawai‘i’s food system, while other foods are nonexistent on the platform, including milk and chicken. A more robust supply requires more farms, but based on the 2022 Dept. of Agriculture Census Report, Hawai‘i agriculture is on the decline, having lost 82,000 acres of farmland between 2017 and 2022.

Hawai‘i has been trying to grow local agriculture for decades. Foreseeing a shift away from a plantation-dominated economy, the state’s Constitution was amended in 1978, requiring the state to designate and conserve ag lands and increase agricultural self-sufficiency. In the more than four decades since, various organizations and initiatives have formed to stop the hemorrhaging of farms and farmlands, with Barecca a beneficiary of many of these efforts.

Along with Farm Link, Barreca started his own farm, Counter Culture in Hale‘iwa, after Kamehameha Schools’ Mahi‘ai Matchup agriculture business plan competition awarded him $20,000 and a five-year rent-free lease in 2015. And since Farm Link’s inception, it has received investments and grants from Hawai‘i Investment Ready, an accelerator for businesses striving to improve the environment and society; Kamehameha Schools’ Food Systems Fund; and the USDA Local Food Promotion Program. In 2021, it joined the Da Bux program—which doubles SNAP benefits, making locally grown produce and poi half-off for beneficiaries—an initiative that addresses food insecurity while also investing in local agriculture.

BHAG bullet point: “Community advocates credit FLH with contributing to the demise of food deserts on O‘ahu and making good food available to everyone.”

To witness the growth of Farm Link is to see how many hands are involved in trying to strengthen local ag. And now, it is also part of the network.

Ironically, to build an online grocer like Farm Link—where consumers buy food without interacting with a single person—requires in-person community building. Sullivan, who joined the company in 2021, has literally chased down Breadshop’s owner on the streets of Chinatown to get him to sell more bread on Farm Link and has met with cattle ranchers and chicken farmers to talk about plans for a mobile slaughterhouse.

For decades, demand for local products has outstripped supply and “if we wanted to achieve our vision, we realized we couldn’t just sit on our hands and wait for all of this amazing organic produce and locally manufactured goods to happen on its own,” Barreca says. “We had to try to build a supply chain … to connect folks to great product that doesn’t exist yet.”

Recently, Farm Link brokered an arrangement involving Kamehameha Schools prepurchasing “a significant volume of bananas,” Sullivan says, to be delivered within the next five years, enabling Farm Link to give Hawai‘i Banana Source “the capital upfront to make the investments they need in the plantings so that they can scale up over time.”

BHAG bullet point: “Food system organizations, local government, and peers point to FLH as a role model and primary driver of the increase of local food production.”

“It’s a really exciting example of supply building, ensuring that there’s more of this thing a year from now than there was today and not being passive and just saying to the producer, ‘We need more of it,’ ignoring the fact that they have the thinnest margins and the highest risk of anybody on the value chain,” Sullivan says. “And we’re assuming that they’re the ones who are going to take that risk? It’s not how farming works anywhere else.”

Hawai‘i has some of the highest land costs in the country, and for 100 years, our island community was so focused on sugar and pineapple that we now lack the infrastructure to support diversified producers, Sullivan adds. “Yet we think that [farmers] should be able to solve it on their own.”

Sullivan has spent her entire 20-year career focused on the local food system, first at Maui Land & Pineapple Co., followed by a decade at Whole Foods building its local purchasing program, and then at MA‘O Organic Farms as the director of development and impact. She’s been around long enough to watch O‘ahu’s last dairy close; to witness Whole Foods scale back its local purchasing; to see the food supply problems laid bare during the pandemic and the sense of urgency and opportunity to fix them fade away.

Yet she’s hopeful. “Progress feels like fits and starts,” she says. “Sometimes, there’s real setbacks when we lose a producer, or when there are changes even in just ownership structure around key infrastructure pieces that feel disruptive—like slaughterhouses. (In 2019, Idaho billionaire Frank Vandersloot took control of Hawai‘i’s two largest slaughterhouses.)

“It all feels so precarious. But that said, it’s also feeling cumulative, like our collective capacity is getting so much stronger. And that capacity is not resting on singular producers, which is how it used to feel, like a one-off success story. Now, it feels more like those success stories are embedded in a more collective fabric. I wouldn’t say that it’s easy still. But there is a fabric.”

Sullivan points to changes in the local agricultural ecosystem over the past five to 10 years. She calls financial backers like Feed the Hunger Fund and Hawai‘i Investment Ready the “interstitial tissue,” and cites the Hawai‘i Food Hub, a network of 14 food hubs, with members that call each other to share insights.

“I’m hopeful [because] of the collective,” she says. “It’s recognizing this isn’t an environment where a singular effort could ever succeed—it will succeed by virtue of the collective success or fail by virtue of the collective failure.”

But there’s no getting around it: buying local is expensive. Local produce such as carrots and mushrooms can be twice the price, or more, of their imported counterparts. It’s the number one complaint of local consumers, according to a survey Farm Link sent out. In the same survey, 62% of customers say they also shop at Costco.

Sullivan says it’s reflective of Hawai‘i’s high cost of living—the highest in the country. People may want to buy local, but not everyone can afford to. But if consumers don’t buy from small-scale producers, which most farms in Hawai‘i are—and those producers are subject to the same high cost of living as everyone else—farmers won’t be able to invest in ways to scale up and bring costs down.

Those carrots? Google videos for “carrot harvester” and you’ll see why imported carrots are so much cheaper than in Hawai‘i, where each carrot is still pulled by hand.

“This is our biggest challenge,” Sullivan says. “And it is where very clear active intervention is required to break the impasse. A lot of the additional interventions will need to be made at the governmental level, capital providers, technical assistance suppliers, the university.”

She says people always ask, what’s the one thing that would make local agriculture viable? “There is no singular thing. That is erroneous; it is an ecosystem and that is the whole point. It is systemic. And solutions have to be as complex and systemic and intertwined as the problem is to have any chance of success.”

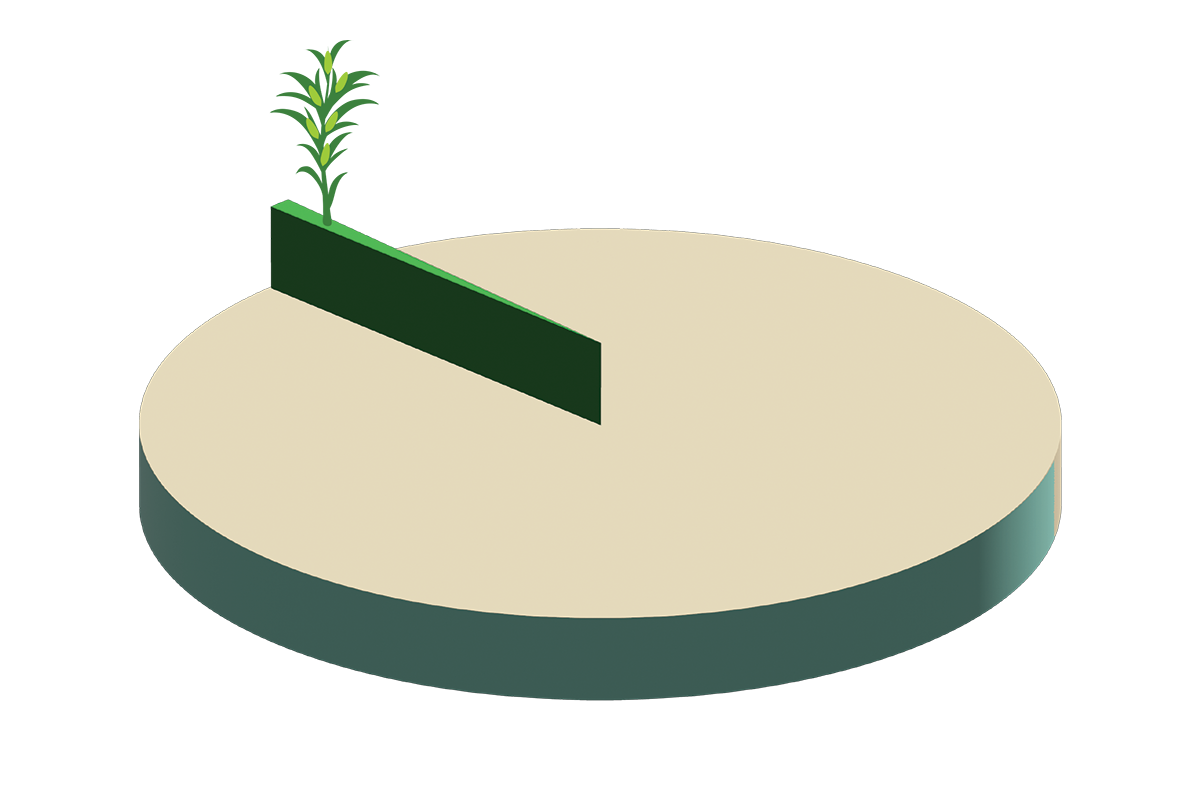

“It’s like asking a fish, ‘does the water really matter?’” Sullivan says when asked why the local food system is so important, especially when judging by the state’s list of priorities—agriculture makes up less than 1% of the state’s budget. “The reason I started working in food 20 years ago is because it was the space where all important things come to meet—our economic health and vitality, our ecological well-being, our cultural source of joy and history and opportunities to perpetuate that, our personal physical health, and our familial well-being. All of those things are impacted by food and how we interact with the production and the consumption of food. So the local food system matters because it’s touching all of those things.”

What keeps her going, what keeps her working in food is that its “shadow side is joy,” she says. “Like the overwhelm is so real and like yes, on the one side it is [about addressing] climate change and pollution and runoff into the ocean and into our streams. And on the other side, it’s delicious and fun and we get to cook it together. So how incredibly awesome that this momentous, hugely consequential space is also joyful and delicious.”