5 Chefs to Watch on O‘ahu

In their dishes and kitchens, these local chefs are helping to shape the city’s restaurant scene.

To be a chef is to be a craftsperson, applying artistry to food. But chefs are also tradespeople, enduring intense physical demands to produce consistent results, all while managing cooks on the line. Despite glossy features—like this one!—it can be largely thankless work. Here are five chefs to take note of, each driven by curiosity and the dynamic nature of the job.

Emily Iguchi

Executive chef, Fête

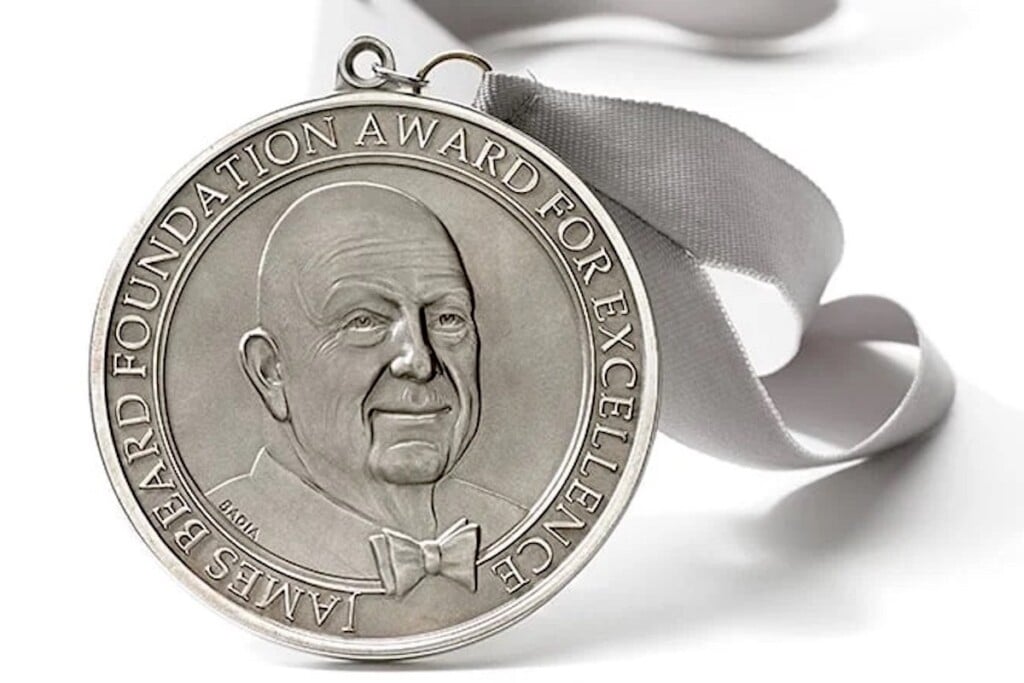

Emily Iguchi’s career has been shaped by tenacity. She started with a lot of cut fingers and kept practicing until she became known as “that girl with really good knife skills,” as another chef described her. Iguchi is now Fête’s executive chef, having helped lead the restaurant to a James Beard Award in 2022.

“Karate Kid is my favorite movie,” she says. “You just gotta keep pushing. It’s about joy in repetition; it’s being excited to do the same thing over and over and do it better every single time.”

To Fête’s menu, a collaboration between Iguchi and chef and co-owner Robynne Maii, Iguchi tends to bring more Italian flavors, as in the house-made ricotta cavatelli with Italian lamb sausage punctuated with olives and preserved lemon. “I’m just very romantic about Italy and Spain,” Iguchi says. “The colors and the sunset and the people [all] come out in the food.” That sunny warmth is especially evoked in Fête’s 15-layer lasagna—delicate house-made pasta sheets layered with eggplant béchamel and mushroom ragu. There’s also a meaty version with venison, pork and beef, and another of chicken, chicken livers and pork.

Originally from Northern California, Iguchi graduated from UCLA, where she joined the Hawai‘i Club. “I was just so interested in everyone that came from Hawai‘i,” she says. “There’s something very happy about the way they lived and shared. There was always food around and they were always playing music.”

She enrolled in Kapi‘olani Community College’s culinary school and worked at Alan Wong’s The Pineapple Room. She then spent 12 years in New York, working at Café Boulud, the barbecue spot Char No. 4, Locanda Verde, and The Dutch. Finally, in 2016, she returned to the Islands. Her husband, whom she had met at Locanda, had been hired to work at Senia, but when they arrived in Honolulu, it wasn’t open yet. They stood on the sidewalk, peering in, when Chuck Bussler, Maii’s husband and co-owner of Fête, walked by. “Hey, looking for a job?” he asked Iguchi. “No, thank you,” she replied, with no idea who he was. Some months later Maii called, and Iguchi became Fête’s sous chef.

“The curiosity never stops,” she says, about cooking and running a kitchen. “It’s not just how to manage people, but to help people understand how to live their life. Like how do you become responsible enough to mise en place your things [and] to mise en place your life, to actually pay rent, to deal with other people, to have good relationships? It’s more than just food.” Which is a very Mr. Miyagi-like thing to say.

2 N. Hotel St., (808) 369-1390, fetehawaii.com, @fetehawaii

“It’s about joy in repetition; it’s being excited to do the same thing over and over and do it better every single time.”

—Emily Iguchi, executive chef, Fête

Arnold Corpuz

Executive chef, Cino

Hawai‘i changed a lot while Arnold Corpuz was away. After he graduated from Farrington High School in 2000, he left for culinary school in Portland, Oregon, and stints in San Francisco and Las Vegas. Two decades later, Jin Hong, a friend from intermediate school days, approached him with a job offer at his upcoming restaurant, and in 2023, Corpuz came home to helm Cino.

“I was surprised how the food here evolved so much,” Corpuz says. “The techniques had evolved—they’re not so simple anymore.” At Cino, he asked his cooks what they ate at restaurants, “to see what Hawai‘i wants,” as if he had landed in a foreign country, and not where he was born. But “that’s why I really enjoy working in the kitchen,” he says. “I’m always learning, no matter what. At this point, I’m still learning.”

In prior years, Corpuz was the executive chef at Eataly and Carnevino and the culinary director of Brezza and Bar Zazu at Resorts World Las Vegas. Without chef Nicole Brisson’s mentorship there, he says, “I wouldn’t have done so well. She gave me space. Because of her, I could really expand my creativity.”

At Cino, Corpuz melds an American steakhouse with an Italian restaurant. He’s particularly proud of his pastas, such as the crab spaghetti, and meats dry-aged in-house, including tomahawk steaks, pork chops and duck.

Preparing the duck is a weeklong process that includes a four-day dry age and a technique similar to preparing Chinese roast duck in which air is pumped between the skin and meat. The duck is served two ways: the leg confited and deep-fried so the skin is as crispy as a chicharron, and the breast pan-roasted with a reduction of port wine and orange juice. The hit of citrus is one of Corpuz’s signature flavors, a jolt of acid to brighten and balance.

A few dishes incorporate Vegas panache, like the tuna carpaccio, what he calls Cino’s style of poke, overlaid with a filigreed tuille spiced with Calabrian chile. But for the most part, the presentations are understated. Corpuz may have found that the food in Hawai‘i is not as simple as he remembered, but the trick, as his chef at Spago Las Vegas used to tell him, is learning how to keep it simple.

987 Queen St., (808) 888-3008, cinohawaii.com, @cinohawaii

“That’s why I really enjoy working in the kitchen. I’m always learning, no matter what. At this point, I’m still learning.”

—Arnold Corpuz, executive chef, Cino

Bao Tran

Chef and co-owner, Giovedì

Bao Tran is not interested in being a purist. He’s also not interested in the maximalist-bordering-on-unhinged Italian dining popping up across the country. What he wants is the space in between, where there’s room for people like him, of Vietnamese descent, and his wife and co-owner in Giovedì, Jennifer Akiyoshi, of Japanese heritage, to make their mark on Italian American cuisine.

Giovedì, their restaurant in Chinatown, is “very Italian-focused, but also we want to celebrate our backgrounds and our heritage,” Tran says. “We wanted to be able to bring some of those melting pot flavors into our cuisine, but not make it gimmicky or kitschy. The hard part about conceptualizing each dish is like, OK, could a Chinese person, an Italian person, eat this dish and recognize their cultures and part of their heritage in this dish?”

His take on gnocco fritto threads that needle. Traditionally, the fried dough is served as a snack with cured meats. When Tran tasted it in Italy, it reminded him of one of his favorite Vietnamese treats growing up, banh tieu, a hollow fried doughnut coated in sesame seeds. So at Giovedì, he pairs banh tieu with prosciutto. For a pork chop dish, he marinates the meat in a char siu marinade, grills it like an Italian steak over charcoal, and finishes it with a fruity and sharp olive oil.

“We don’t want to offend anybody, but at the same time, these cuisines mash up really well,” Tran says. “If treated with respect for the ingredient and respect for the culture, you can create something really beautiful.”

He credits his time with Major Food Group, whose restaurants include the modern Italian American Carbone in New York, as one of his greatest influences. Virginia-born Tran spent about a decade in New York before moving to Hawai‘i, where Akiyoshi is from and where they helped open Mad Bene.

Akiyoshi runs Giovedì’s dining room, but she’s also behind “Mrs. Tran’s tiramisu,” which pokes fun at the nonna-in-the-kitchen trope. People assume “Mrs. Tran” is Tran’s mom. Rather, it’s an inside joke, a nod to the time Tran’s attempt to impress Akiyoshi by making tiramisu turned into a goopy disaster. She spent the entire next day preparing seven different versions in pursuit of perfection. It is the most traditional dish on the menu. Tran’s skill is not just knowing how to combine cultures on a plate. It’s also knowing when to leave them alone.

10 N. Hotel St., (808) 723-9049, giovedihawaii.com, @giovedirestaurant

“If treated with respect for the ingredient and respect for the culture, you can create something really beautiful.”

—Bao Tran, chef and co-owner, Giovedì

Casey Kusaka

Executive chef, Lovers + Fighters

Casey Kusaka likes to say he was born on a Zippy’s banquette. His parents met at Zippy’s—his mother was a server and his father one of its first employees, working with its founders to open locations across the island—and Kusaka remembers always falling asleep on the banquettes.

Since then, he hasn’t strayed far from restaurants, whether cooking at Zia’s in Kāne‘ohe, where he was born and raised, or waiting tables at Momofuku Ko in New York. He is a rare professional proficient in both the front and back of the house. The straddling of worlds shaped his career: Kusaka attended KCC and the Culinary Institute of America and worked as a noodle cook at Momofuku Noodle Bar, slinging almost 500 servings a night before turning to the front of the house, including a stint as the general manager at two-Michelin-starred Californios in San Francisco. He came home for family.

“I got a chance to work at some really fine dining restaurants,” he says. “But I think deep down in my heart, I like the ugly, delicious food. I like the plate lunches, and I like cooking comfort food that has soul.” So “being surrounded by my family and the original influences of cooking for each other … my mind and my heart [said] I needed to get back into the kitchen.”

At Little Plum, part of the Lovers + Fighters restaurant group, Kusaka taps into memories of turkey jook after Thanksgiving with his mushroom and chicken rice porridge, topped with a shoyu-marinated egg and shredded confit chicken crisped on the plancha. A menchi katsu resembles a loco moco but comes with a panko-breaded and fried hamburger patty, an example of how he says he likes to “weave in different techniques and flavors while keeping it light and fun and whimsical. I always check in with my cooks, like, ‘Does it taste good? Does it feel good making it and does it make you feel good eating it?’ If you answer yes to those questions, no matter what it looks like on the plate, someone’s gonna enjoy it.”

2752 Woodlawn Drive, (808) 888-0330

Jason Kiyota

Chef-owner, Threadfin

For eight years, Jason Kiyota’s The Food Company Café in Kailua was a destination for those in the know. By day, Kiyota served grab-and-go lunches. At night, he set the tables and shaved black truffles over Hokkaido scallops and porcini risotto, or sprinkled bubu arare over creamy curry crab pastas. He often served moi—his favorite fish since his father taught him how to catch it with a bamboo pole when he was 5—searing it for a crisp skin and bathing it in a saffron nage with melted leeks. Kiyota cooked with a few induction cooktops and a small oven until 2019, when he decided to open his own place in Kāhala. But the pandemic hit, lease negotiations dissolved, and Kiyota turned to catering.

Now, finally, he has a place of his own. Threadfin, another name for his favorite fish, opened last September in Kapahulu’s Kilohana Square, more polished than his previous space, but just as intimate with 30 seats. A monthly changing prix fixe showcases Kiyota’s melding of flavors, which have evolved from Asian with French underpinnings to increasingly global influences, as with a steak over ras-el-hanout cream or scallop aguachile paired with a lime-leaf-dusted rice cracker.

If there is one through line, it would be Thai seasonings, informed by Kiyota’s year in Thailand after graduating from the KCC culinary school. He attended culinary classes at an agricultural college in Bangkok, frequenting food stalls in his free time. A khao man gai vendor under one of the city’s Skytrain stations made the best chicken and rice he ever tasted.

“It’s all by eye, and the taste is so good and so consistent,” he remembers. “It was kind of shocking knowing that somebody can make a living off doing one dish.” Afterward, he traveled the country to explore its regional cuisines, from the thinner broths in the north to the more coconut milk-heavy curries in the south.

Back in Hawai‘i, while working in kitchens at the Royal Hawaiian, Sheraton and Halekūlani hotels, Kiyota continued to travel and cook—heading to a two-week food festival in Bolivia and chef courses at the Culinary Institute of America in Napa. A small restaurant was never his intention. Kiyota recently took over the feng shui shop next to Threadfin, expanding the restaurant’s dining room and adding an à la carte menu. Now, he can invite more people to the table.

1014 Kapahulu Ave., (808) 692-2562, threadfinbistro.com, @threadfinbistro